Due to production error, some of the photos featured in Passing Again appear much darker than the photographer intended. A photo gallery has been posted on this site to provide readers with more accurate reproductions of these photos. This gallery can be found on the Passing Again: A Photo Gallery page which can be found by using this link: http://ibeambooks.com/355-2/

* * * * *

AUTHOR’S Supplement for Passing Again

For those readers puzzled by the possible relationship between AUTHOR LeClair and character LeClair, the publisher has compiled this brief supplement. A reminder: the Terminal Tours website mentioned earlier https://sites.google.com/view/terminaltours/home has first chapters from Passing Off, Passing On, and Passing Through. Those unhealthily obsessed with the AUTHOR can find his recent essays and reviews [“More What to Read (and Not)”] and his writings about Trump [“Literature Against Trump”] on Medium: https://medium.com/me/stories/public .

Supplement

Table of Contents

Epilogue by Kinga Owczennikow

Interview of Tom LeClair

The Curse of the Zombie Book by Tom LeClair

Second Acts by Tom LeClair

Pynchon, the Pandemic, and Me by Tom LeClair

* * * * *

Epilogue

by Kinga Owczennikow

This is not a translator’s Epilogue, though it has been translated, written first in Polish, then translated into English by the author who is more comfortable speaking English than writing it. Nor is this Epilogue what Michael might call an AUTHOR’S note. Since I was a participant in and a witness to some of the conversations in Passing Again—and an important exchange about it—Michael and Tom suggested I write this brief account for the new edition of how the book came to be—and almost didn’t.

After changing their countries of residence, neither Michael nor Tom wanted to write a full memoir, so they had the idea of publishing an “archive.” Fortunately, both writers keep journals and could reconstruct from their notes the “tapes” that appear here. Whoever had the better notes and better memory of a conversation would write up the “tape” of it and send it to the other to approve. If they ever become famous, they joked, scholars could poke around in their journals and compare the notes there with the dialogues printed here. I did not “record” in my journal any of the Athens conversations in which I participated, but I can say that my presence (in both words and photographs) has been accurately and fairly represented in Tom’s one “audiotape” and Michael’s two “videotapes.”

Once Michael and Tom had e-mailed texts of their conversations back and forth and had made changes or corrections, they decided to include past work (“In the Woods” and “Pleasure Tour,” “The Other Guy” and “Miracle Tour”) and introductions from works in progress—Michael’s novel about Johnny Appleseed, Tom’s book about my photography—influenced by their trip to Athens. These inclusions led to some small revisions, what Tom called “backfilling,” but both agreed the revisions did not affect the authenticity of the “tapes” here.

When the draft of Passing Again was finished, Michael and Tom wanted to get together again to talk through the final version. Tom and I invited Michael and Kara to Warsaw. They countered with an invitation to a warmer Mexico City, where Kara and I spent most of our ten days out photographing while Michael and Tom sat in a cafe and made a final pass through the manuscript. They even decided on an image they would suggest for the cover: Janus, the god of doorways, passages, and beginnings, something of a trickster who probably appears in the first photo in the book.

All seemed to go well until our last night there when the four of us went to a Lebanese restaurant for dinner. Somehow the North African food and, perhaps, the wine led to the following conversation, to which Kara and I listened with growing alarm.

Tom said to Michael, “In the e-mail you wrote to Kinga and me, you said the ‘Revenge’ woman wore clothes that reminded you of Algerian women. But I just now remembered: you told Patrick in Passing Away that you’d never been to Algeria.”

“Have you been rereading all our books to fact check?”

“No, I just remembered it, as another example of your contradicting yourself, undercutting yourself.”

“Of course I’ve been to Algeria,” Michael said. “The woman I rescued is now living and writing in the States.”

“Her being outside Algeria doesn’t mean you went there and rescued her, not unless she’s been writing about you.”

“She writes mostly in French, which I don’t read. But you could look her up on the Internet and get in touch with her if you don’t believe me.”

“So why did you lie to Patrick?”

“He had been busting my balls about making up stuff, and was suspicious about my going to Algeria to save a stranger, so I thought I’d make a dying man happy if I ‘admitted’ I hadn’t gone.”

“Yeah, okay, but why put that false ‘confession’ in Passing Away?”

“Because it was the truth.”

“Your lie to Patrick was the truth?”

“The lie happened, so it’s the truth.”

“And are you still claiming your e-mail about your meet with the ‘Revenge’ woman in Algerian garb is also the truth?”

“Why would you question me now over what that woman was wearing?”

“Because after you said you feared meeting with ‘Revenge,’ I wondered if the point guard chickened out, never went to the meet, and made up a story to save face and make Kinga and me happy. Maybe it was the first-person point of view that made me suspicious.”

“Did you expect a photo of the woman and me? Haven’t all of the tapes been prepared by ‘first persons’ who create an illusion of recording?”

“There was also never any contact from the group after your meeting.”

“Right, and the last time I looked the Parthenon was still standing. Why, at the last minute over dessert, are you trying to expose me again and fuck up a book we’ve finished? And, I might say, a book we should make some money from.”

“Because I want the book to be true. The photos are true. I want the words to be true. Anyone who has read Passing Away may suspect your words about that meeting, what the whole of Passing Again was leading up to.”

“First, nobody is going to go back through our other four books to check the facts in this one. Second, our archive isn’t ‘leading up to’ anything. It doesn’t have a plot. It’s just a series of conversations and images that readers can put together any way they want.”

“That may be true for you, but not for me. This could be the last book I finish, and I want it to last. It has a form. It tells a story. I want it to be true. Certainly, we were deceiving each other in Athens, but we eventually told each other the truth about our lying. Your meeting with ‘Revenge’ now seems like it could be a fiction, an unadmitted lie. If so, it poisons the book, undermines the authority of the photos, and turns Passing Again into another of your fictionalized memoirs. Maybe we should just put the manuscript in a drawer and get on with our other separate projects.”

“You’re not going to fuck me out of money like the Greeks did long ago. You know how I feel about money.”

“I certainly do. Before you asked me if I were terminal you asked me for money from our conversation five years ago.”

“Crass-ass Keever, free to be.”

“‘Be Like Mike.’ ‘Republicans buy shoes.’”

I had no idea what Tom meant by those last three-word sayings. Fortunately, at this point Kara came to the rescue and maybe “saved” Passing Again. She said, “Tom, don’t you remember that I went to Algeria with Michael? I have some photos of the Martyrs Memorial in Algiers I could show you.”

“Jesus, Kara, I am so sorry,” Tom said. “There’s a lot I don’t remember in those books. That’s one reason I invited Michael to come with me to Athens.”

Tom turned to Michael: “I’m apologizing for this Algeria business. I’m so used to you lying I guess I overreacted to the Algeria reference.”

Michael was silent. He appeared to have what he called his game face on. I shouldn’t speculate, but he may have been impassive because money was at stake.

Kara said to Tom, “You know Michael has been to Egypt. Why not just change Algeria to Egypt and no careful reader of the Keever books will be suspicious of Passing Again.”

I agreed with Kara, and told both Michael and Tom, “You have put too much time and work into this book to abandon it now.”

“Double-teaming peacemakers, Tom,” Michael said. “Two on one. Wait, make that three on one.”

“I’m not going to call you a liar, Kara. So we’ll change Algeria to Egypt and preserve Michael’s long-delayed veracity.”

“And his share of the possible profits,” Michael said, with a grin on his face.

Unlike the translator of Passing Off, who wrote his Epilogue to question Michael’s veracity, I have written my Epilogue to support the veracity of Passing Again. I realize my account of the last conversation may make readers suspicious of that veracity, but I include the dialogue to demonstrate the authors’ scrupulous commitment to creating an archive of both lying and truth. Given the preponderance of both these elements in Passing Again, I wouldn’t be surprised if detective readers tried to contact Kara Schmidt to check my veracity here. So I will take my lead from both Michael and Tom, who documented their presence in Athens, and include a photo—my seed of reality—that at least documents my visit with Tom to Mexico City. Shot with Tom’s cell phone by a helpful stranger, the photo shows Tom and me on the flat roof of Diego Rivera’s studio, which was connected by a bridge to Frida Kahlo’s studio, an odd doubling arrangement for those two artists. I am not given to personal revelations, but will say that Tom likes this photo, he says, because I appear to be blissfully, eye-shuttingly happy to be holding his hand. I tell him I probably forgot my sunglasses and am averting my eyes from Mexico’s bright light. Photos don’t lie, but they—like Passing Again—are subject to a play of different speculations and reflections.

* * * * *

Interview of Tom LeClair

The first of thirteen books by Tom LeClair was a collaboration with Larry McCaffery, a collection of interviews with American novelists entitled Anything Can Happen (1981). Now after four books of literary criticism and seven novels—four of which have the former basketball player Michael Keever as putative author, narrator, and protagonist—LeClair has returned to collaboration and conversation in Passing Again. Keever’s books—Passing Off, Passing On, Passing Through, and Passing Away—are his memoirs. LeClair’s non-“Passing” novels—Well-Founded Fear, The Liquidators, and Lincoln’s Billy—are insistently fictional, having nothing to do with his personal life. But at 75, the “LeClair” in Passing Again wants to write about the year he lived in Greece, shifted from criticism to fiction, began to write Passing Off, and invented Keever. Because some of “LeClair’s” memories of 1991 are dim, he asks Keever to accompany him to Athens where Keever also changed his life that year and became a hoop star known as “The Greek Key.”

The four previous “Passing” novels had a fake title page with Michael Keever as the author. The fake title page of Passing Again has Keever and “LeClair” as co-authors. The subtitle of their book is “An Archive”—materials each can draw on for their memoirs. Early on these memories are confessions of cheating as husbands and writers, deceptions that come back to plague both men in the present of Passing Again. Partial doubles, they involve themselves in plots duplicating the past as life imitates earlier memoirs and fictions. As the title of Passing Again suggests, the novel is like a capstone to Tom LeClair’s Keever novels—and to that first collaborative book of talk.

Int: You know what I’m going to ask you first, right?

TLC: And you know what I’m not going to answer.

Int: So let’s get it over with: Passing Again is a double memoir of your character Michael Keever and Tom LeClair. How much is factual?

TLC: Everything from Keever, I think, though he is a practiced liar to whom LeClair gave autonomy. The Epilogue suggests Keever may have invented the climax of the plot. That does seem like something he would do.

Int: And what about Tom LeClair?

TLC: I suppose you’re asking the figure Keever calls the AUTHOR, the person whose name is in capitals on the first title page. A good deal of what the AUTHOR has Tom LeClair say in the text is probably factual, though it’s possible he may be lying to Keever at times.

Int: Okay, so we have two liars in the text. Please tell me the AUTHOR is not a liar in this interview.

TLC: Back when I was a kid, I was much taken by Wayne Booth’s Rhetoric of Fiction that posited several fictional frames: the author who pays taxes, the persona the taxpayer creates when he or she writes a novel, the narrator who may share some qualities of both the persona and the taxpayer, and the characters who may also share qualities or histories with all of the aforementioned. I’m honest when I pay taxes, but as the AUTHOR behind the five Passing books I’m a point guard (like the deceptive and manipulative Keever) who follows his coach Jacobs’ directive: “Bring ‘em to you, fuck ‘em up.” In the past, I’ve initially offered readers easy genre pleasures and then confuted their expectations of more, using unreliable narration to make readers uncertain about what Keever and the AUTHOR are up to. Passing Again is probably not so easy—and more mysterious—at the beginning. I’m not a mystagogue or writer of mysteries, but I agree with my mentor, Don DeLillo, who told me that a novel should be a “mystery, in part.” I’m also not a recluse like Pynchon or like DeLillo used to be, but to tell you too much would probably compromise that mystery.

Int: Confuting expectations is not a way to make friends.

TLC: Not many but maybe a few good ones. When expectations are confuted, readers examine their validity and value, and perhaps reexamine themselves, their possibly conditioned ways of construing novels, media, and the world. Like Nabokov, the point-guard author considers the reader as an opponent in the game of fiction. If the author is clever enough, the reader may be trapped in a mobius-like Greek Key where the reader goes round and round again in the mystery-minded text with—this AUTHOR hopes—some pleasure. Along with basketball, Pale Fire and its doubling were on my mind when I was writing Passing Again. I suppose one link between the two books is the question: how does literature influence us? Mystified by some photos he receives, Keever concludes that the function of photos is to produce uncertainty, the “then again” response: “Look again, think again, read again,” he says. I think those are also the “lessons” of literature and, possibly, Passing Again.

Int: You have a character praise “pleasure without pressure.” Is this the kind of pleasure you hope to offer?

TLC: Yes, speculative and interpretive exercise with no heavy lifting or heavy breathing, with not much at stake since Passing Again doesn’t purport to explicit political or social relevance. Put a character and his creator in the same space and you’re in the realm of fantasy or imagination where real-world pressure is relaxed. “No game, no gain,” Keever likes to say. LeClair in the novel says he hopes to have “fun” in his final years. “Me to play” from Endgame is the AUTHOR’S epigraph. If not political or social, perhaps Passing Again does offer some psychological and cognitive relevance with the book’s exploration of play and “the novel,” by which a character means the literary form and the word meaning “new.” And there’s some really old material in the novel, as old as consciousness I guess: the fear of death.

Int: Would you call Passing Again a metafiction?

TLC: Metafiction and metamemoir and metaphoto.

Int: Keever plays basketball, LeClair plays with fiction, the third character, a photographer called “K,” seems to play with her viewers. Did you have fun writing Passing Again?

TLC: I shouldn’t admit the following because I believe readers expect memoirs should have powerful psychological motivations. Me, I had materials: some pieces already published, others unpublished, a lot of photographs, a short story about Keever and LeClair, and an odd doubling quirk in my personal history. I thought maybe these materials would fit together if the AUTHOR had enough ingenuity. So, to get to your question, yes, it was fun assembling the book—using some materials again and writing the new material. I liked the collaboration. The characters collaborate with each other. I was collaborating with myself.

Int: Do you think the book is fun for readers, too?

TLC: You know about the revenge tragedies that influenced Shakespeare. I think of Passing Again as a “revenge comedy” and hope it will give readers some laughs.

Int: Even if they feel “fucked up” by the point-guard author?

TLC: [Laughter.] Let’s rename the readers’ experience to “pleasurable cognitive dissonance, the effect of unthreatening novelty.” The first friend I sent Passing Again to—a voracious reader of memoirs—didn’t see it that way. She hated Passing Again. She said it was a novel masquerading as a memoir. Or is it a memoir masquerading as a novel, an AUTHOR both revealing unsavory parts of his life and dancing around them with fictional devices? Or is it neither? The subtitle is “An Archive.” The book collects some materials for possible future memoirs by Keever and LeClair, but Again also has a romance, some travelogue, the first chapter of a novel about Johnny Appleseed, the introduction to a book on photography, and some stichomythia pretty much for its own sake and the reader’s amusement.

Int: There’s a sexual relationship in the novel between an old man and a youngish woman. Maybe your friend objected to that in the age of “Me Too.”

TLC: Keever warns LeClair he better not put intimate details into the memoir he plans to write because “you’ll have your balls removed by some feminist reviewer.” There is, indeed, as Keever continually notes, a very improbable romance in Passing Again. LeClair responds to Keever that black swans do exist and that life doesn’t need to be as probable as fiction or memoir. Pretty much everything in the book could be called improbable—a character and an author going on a road trip to begin with, the inclusion of numerous photographs, two doubling plots, multiple unanticipated endings. Keever is known for creating in the air. That is, jumping and improvising before he comes down. I’d not thought of this before . . . but maybe the various improbabilities are laid on by the AUTHOR to make the improbable romance seem less improbable. “Let us sport us while we may” says the seducer in “To His Coy Mistress.” This novel, partly about Marvell’s kind of sporting and the sport of basketball, is like an improbable sport of nature, a mutant or hybrid.

Int: I know you don’t much like conventions, but would you mind if Passing Again were called a love story?

TLC: I’d prefer love “stories”: Keever’s love of basketball, LeClair’s love of Athens, K’s love of photography, and, perhaps, the love of author and photographer. I’ll leave it to readers to find out what the love stories have in common.

Int: And what about the AUTHOR’S love of literature? There are quite a few buried allusions and literary references in the novel, including one to Aristophanes’s The Birds and a couple to your friend DeLillo.

TLC: Love of and suspicion of fiction, I think. Passing Again uses its photographs to stage a quarrel between images and words, the limitations of both, particularly in the telling of stories. For decades, under the influence of William Gass (both his essays and his multimedia Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife), I tried to persuade my university literature students not to picture what they read in fiction because they were filling in their pictures with their own experiences. I pleaded with them to focus on the verbal connections across the text. I was never successful. By including photos of the principals and some of the setting in Passing Again, I hoped to give fiction readers the pictures they wanted so they could concentrate on the text. Or, as Nabokov says, “not text but texture.” Since there are something like 50 photos in the book, memoir readers should be happy about real-world referentiality but may wonder if so many could be mocking their desire for documentary truth. What will they do, for example, with the photo of Michael Keever? Talking with photographer K, Keever says “Photographs don’t lie, but photographers lie about them.”

Int: You mention William Gaddis in the novel. Was he, along with Gass, an influence?

TLC: I’m glad you mention that. I’m a great admirer of Gaddis’s JR which is about 95% dialogue. I’d say about 75% of Passing Again is dialogue in the “videotapes” and “audiotapes” that the male characters are preparing for the archive they believe will help them write their individual memoirs. The “excess” of dialogue is part of that conflict between images and words I mentioned before. Since almost all of the dialogue is in Athens, some of it is peripatetic, and more than a little is sophistical, I guess you might also be reminded of the Platonic dialogues.

Int: Unlike many novelists, you don’t seem to mind talking about influences.

TLC: Maybe because influence is a subject of the novel. LeClair says he likes the idea of the author as “influencer” rather than as creator. As I’ve said, Passing Again was, to some extent, assembled rather than created out of what LeClair calls “thin air.” Most novels called realistic are assemblages of conventions and stereotypes and probable actions, but most novelists like to pretend their works are original creations from the smithies of their souls. A more honest approach is to admit the influences and try to influence readers without employing the hidden conventions of realism or the memoir. Influence readers’s understanding of influence, including how a novelist’s invention might influence the novelist’s mind and life. We know how art imitates life. I wanted to look into how life imitates art and, more significantly I believe, how life may imitate or duplicate fictive-seeming life, replay it. Sports fans will be familiar with “instant replay.” I was going for “distant replay.”

Int: The form of Passing Again is like a scrapbook. Is that an imitation of life?

TLC: It’s a scrapbook with a lot of empty pages. Maybe Passing Again is more a reflection of what all novels actually are than an imitation of life. Writers try to minimize awareness of what is left out of their fictions. Passing Again minds the gaps. Early on, you get two sections of thick discourse about the youth of Keever and LeClair, the kind of discourse you would get in a traditional memoir. There is nothing like those two sections until very near the end of the book. That discourse has been left out, so readers will have to adjust their expectations to the gaps: see again, think again, maybe read again. They may have to do it all over again when they get to the probably surprising endings.

Int: You said earlier that Passing Again didn’t have much social or political relevance, but what about the environmental material?

TLC: Thank you for asking. I’ve said I made Passing Off a conundrum so that while the ideal reader was rereading and rereading to resolve narrational reliability, I’d be sneaking my early warning about global warming into his or her consciousness. The same strategy is in play in Passing Again where ecoterrorists are influenced by the ecoterrorists in Passing Off who want to bring down the Parthenon. To prevent reality from imitating fiction, Keever and friends need to collaborate to create a green alternative to terrorism. I think their solution may be more ingenious than the environmental critique in Passing Off. The solution stresses rejuvenation—a repeated concern in Passing Again—rather than deconstruction.

Int: I think you’ve said Passing Again is a stand-alone work, but its setting in Athens and its environmental plot link it pretty closely to Passing Off.

TLC: Passing Again tries to articulate within itself every objection to it. Keever tells LeClair he is confessing his hideous past (thank you David Foster Wallace) to bring readers in to Passing Off and his other novels. Maybe so. I do believe Again can stand alone . . . but will be enriched by Off. Again is much about doubling or duplication—in characters, in actions, in the relation of books—so it probably relies more on an earlier Keever book than any of the others. Of course, for a full appreciation of Again one should read all four of the earlier books.

Int: You have often praised what you call “monsterpieces,” huge excessive novels such as Gravity’s Rainbow, Infinite Jest, House of Leaves. Do you think the five Keever novels add up to a “monsterpiece”?

TLC: The three you mentioned are extremely original works, have identifiable monsters within them, and were written by geniuses. I’ve been working within semi-popular genres—sports novel, travel novel, academic novel, historical novel, and now postmodern novel—and Keever is no genius. Neither am I. Keever wonders why LeClair keeps coming back to him. LeClair says he admires Keever’s “resilience,” his ability—think maybe Huck Finn—to lie his way out of situations. If no genius, maybe I’m resilient, able to lie myself into and out of genres. There are no monsters in the Keever novels, but they may be a monstrosity of unreliability that even the AUTHOR is uncertain about.

Int: If not a “monsterpiece,” is Passing Again like a capstone to the Keever novels?

TLC: An Epilogue in Passing Off causes many of the problems in Passing Again, which has an Epilogue online, on the publisher’s website. Maybe this novel, which is probably my last, is an Epilogue to all my novels, not just the Keever novels. All of my fictions are first-person and to some extent unreliable narrations. More than any of them, Passing Again explores reliance, what anyone can rely on.

Int: Why do you think reliance is so pervasive in your fiction?

TLC: Keever suggests it’s because LeClair is an unreliable man, maybe not as tricky and deceptive as Keever but still not to be trusted. But I’m pretty reliable—consistent—in my criticism, so maybe all the novels have a metafictional confession or warning like the Lying Cretan’s admission. “You are reading a lie. Don’t rely on a lie.”

Int: After playing with memoir in Again, has the AUTHOR thought about writing a serious memoir?

TLC: I thought Passing Away would be my last fiction. It’s final word in “enough,” also the last word of Rabbit at Rest. Passing Again exists because at the age of 75 I was given an improbable rejuvenating gift by life. Probably just one of those to a customer. It’s to that gift that Passing Again is dedicated. I believe there’s enough “memoir” in Again to satisfy me—if not readers who want to know what really happened after the ending of Again and what the AUTHOR is really like beneath his point-guard assumed identity. Very near the end of the dialogues, LeClair tells Keever that after all their time and talk he really knows very little about LeClair. Ideally, Passing Again and this interview reveal just enough about the AUTHOR to interest the reader in the book itself, its internal relations not external revelations. But who knows? Perhaps in the months to come I’ll feel like filling in some of the blanks in the AUTHOR’s life.

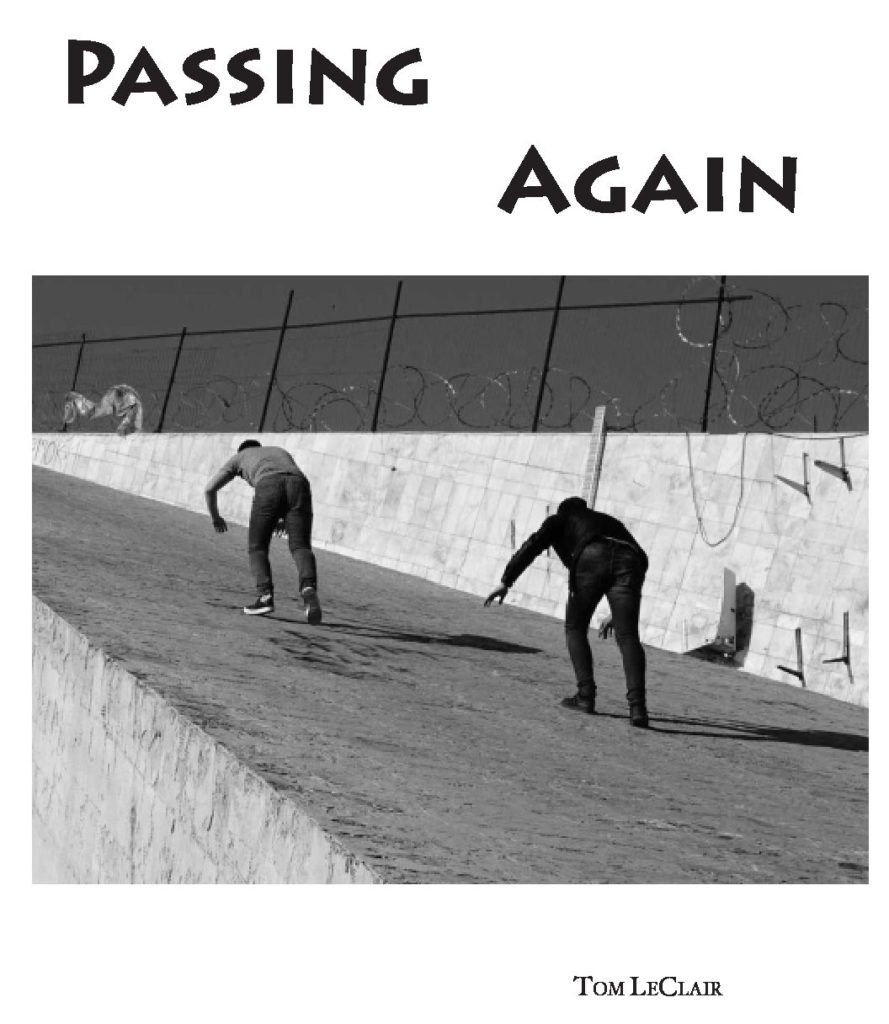

Int: As for “external,” would you comment on the cover of the new edition?

TLC: It’s a photograph by K. It’s hard to tell who is being pursued in this doubling photo. Is LeClair pursuing Keever, or is Keever pursuing LeClair?

Int: One last thing. I looked you up on Wikipedia. Your middle name is Edmund. “TLC” are not your initials. If I am “Int,” you should be “Nov.” Not capital letters that assert some primacy over my lower case letters, and, given your desire to “fuck up” readers, certainly not letters that stand for “tender loving care.” “TLC,” in other words, is a self-congratulating fiction. And the shared caps suggest that even the AUTHOR may be a fiction. I’ll be asking you to produce a photo of your passport to document your identity before I submit this interview for publication.

Nov: I think that’s enough.

* * * * *

The Curse of the Zombie Book

by Tom LeClair from Full Stop (2021)

In Don DeLillo’s Mao II, the novelist Bill Gray describes the manuscript he has been working on for many years, in “a bug-eyed race” against death:

[He] saw the entire book as it took occasional shape in his mind, a neutered near-human dragging through the house, humpbacked, hydrocephalic, with puckered lips and soft skin, dribbling brain fluid from its mouth. Took him all these years to realize this book was his hated adversary. Locked together in the forbidden room, had him in a chokehold.

In a Paris Review interview William Gass said, “I publish a piece in order to kill it, so that I won’t have to fool around with it any longer. . . . As soon as I finish something, it’s dead.” It took Gass decades to kill The Tunnel, which Robert Alter called a “monster of a book,” 600-plus pages of “adipose verbosity . . . and intellectual flatulence.” Bill Gray never killed his monstrous manuscript; he ran away from it instead and died soon after.

It may seem self-pitying (or self-aggrandizing) for writers to personify a manuscript, but maybe novelists can be excused if it’s a long-term project or a lengthy book, or if their protagonist and narrator is a “moral monster,” as Gass’s William Kohler, an historian of Nazism, has been described. If not quite as monstrous as Kohler, DeLillo’s reclusive, Salinger-like novelist exploits others inside and outside his “bunker.”

I wonder how John Updike came to feel about his Harry Angstrom, introduced in Rabbit Run in 1960 and killed off thirty years later in Rabbit at Rest. Rabbit had his faults, but he was not a monster, and Updike may have freely chosen to keep returning to him. Unlike Mark Z. Danielewski’s monster project called The Familiar, which the author planned to release in 27 volumes, the three novels following Rabbit Run were probably not projected by Updike when he was writing Rabbit one. Asked about the death of Rabbit, Updike has said it was an authorial imposition, but of the character’s own making: his unhealthy diet and general weariness with life.

I was thinking about these matters when writing my fifth novel about my former basketball player Michael Keever, the protagonist, narrator, and putative author of the “Passing” novels that began with Passing Off in 1996, Keever is often a deceiver and sometimes a liar, but none of his acquaintances calls him a monster. In this latest novel, Passing Again, Keever and the author go on a road trip together and have some conflicts, but at the end the author character considers Keever a “friend.” So do I. I’d write a novel without Keever, then return to him because I enjoyed his non-literary voice. I have no desire to kill him off. Even if I wanted to, I might not have the opportunity, since I’m 77. Actually, it pleases me to think Keever will still be alive when I’m dead.

It’s not news that for some novelists manuscripts and characters become tedious if not monsters. Much more widespread—possibly affecting every writer—is the post-publication appearance of monsters. That is, a released book returning as a zombie to plague the author. Even though the author believed the work was killed by publication, absent from bookstores, and either buried with its reviews or pulped (cremation-like), it rises to remind the author of its flaws. And I don’t mean just books about zombies such as Colson Whitehead’s Zone One but all books by writers still alive and not in late-stage Alzheimer’s.

Zone One is about a future zombie apocalypse, where Whitehead describes two kinds of zombies that suggest how dead books may affect their writers. The “skels,” short for skeletons, are your traditional, aggressive, flesh-eating zombies. They are like books that pursue authors with recriminations night and day, year in and year out, probably an extreme. More apposite are the “stragglers.” They are figures frozen into immobility and cognitive blankness, losing flesh while waiting to be “put down” like a sick pet or a bad book. The first zombie Whitehead’s protagonist remembers killing is his high school English teacher, suggesting that Whitehead might have some zombies in his past.

Zombie books don’t need to wriggle out of their jackets and climb off the shelves to make their bite felt. The author could be working safely at their desk or drowsing in bed, and remember some improbable situation or weak sentence—or even just one damned wrong word—and the presumed-dead book feels somehow still half-alive, existing like Bill Gray’s “near-human” on the author’s hard drive, waiting to be healed of its wounds, hoping to be more alive by consuming, if not the author’s fleshy brain, some of the author’s fiction-making brainwork. The author may feel publishing the manuscript was a mercy killing, performed before the flawed manuscript got any worse. Now months or years later, they may feel it was premeditated murder, the manuscript prevented from maturing (every possible revision considered, every improvement made), and dying peacefully of natural causes.

The zombie-plagued author believes nothing can be done about the book’s perceived failures and so attempts to assuage their own guilt: “I didn’t mean to kill it; I wanted to release it into the wild, give it a chance.” “It was not perfect, but it was as good as I could make it when I was that age.” “Look, I’ll admit it, I needed the money.” “I had a much better book I wanted to write.” Maybe the author gives away all of her or his copies, skips it in their Wikipedia entry, refuses to let the book be released in paperback (as Don DeLillo did for a time with his first novel, Americana). Or the author tries to erase the book, as did a novelist I reviewed years ago who was promoting a book as a first, although he had published one before. But the zombie remains, periodically returning despite the author’s defenses and machinations. A zombie book, unlike “real” walking and talking zombies, can’t be killed. It’s there deep in Amazon and deep in the writer’s brain. No wonder one has to destroy the zombie’s brain to kill it. One just has to hope that—unlike the buried-alive sister in Poe’s “Fall of the House of Usher”—the zombie doesn’t emerge from the depths and kill the person responsible for the premature burial.

Perhaps authors should go easier on themselves, accept their earlier selves who wrote those embarrassing first and second novels, admit that even perfectionists can change their minds, be proud that they are progressing as artists. People change, minds change, skills change. The trouble is, as a friend of mine said, “the fucking book doesn’t change.” Readers are not likely to change their judgment of some weakness just because the changing author has published more books. And if readers question their own evaluation—want to give the author the benefit of the doubt—they can go to the Internet and look up reviews of the book. It may moulder away, left behind in some beach motel, but a negative review is permanent on the Internet, a source of half life for the zombie.

One wonders if the current zombie craze is screenwriters and novelists externalizing their guilt and disgust, projecting them out onto the unwitting population at large. Yes, people feel guilty about what they have not done in the past, and people may even be living with others to whom they have done guilty things, but memories and other humans don’t have the persistence of the zombie book, which will outlive—if that’s the right word—the dead author if they’re not careful to destroy journals, diaries, or correspondence confessing their doubts about the book’s quality.

I became intensely aware of the zombie book—actually four of them in my case—when I had to re-read the “Passing” novels in preparation for Passing Again, which, as the title implies, has a certain amount of repetition, or revivification. I was happy enough with the way Keever developed, and I sometimes surprised myself with the vigor of his hoopster’s voice, but I wondered why I had been satisfied working in popular sub-genres—the sports novel, the travel novel, the academic novel, the historical novel. DeLillo had done something similar—initially occupying and then transforming genres—and I tried to tell myself that I was resilient, like the shifty and ever-shifting Keever, and yet the “Passing” novels seemed like they could be a quartet of zombies, not just books with small flaws but super zombies that could collaborate to consume the new novel.

My evasion was to make Passing Again a mock memoir, a book that initially confessed the moral and aesthetic sins of Tom LeClair but that eventually became a collage-like postmodern fiction about photography and ecology sure to be unpopular even if done with satisfactory ingenuity. I thus killed the popular autofiction before it could be a sub-genre zombie. I know I will still get visits from the first four “Passing” novels, but I’m hoping that Passing Again was written with sufficient zombie consciousness to keep it from tormenting me in the future. Of course, I know there will be mini-reminders of Again’s inadequacies. I just want to avoid being assaulted, five zombies gathered outside my window pleading for a better life. In their case, a wholly different life independent of popular sub-genres.

Some heavy-hitting authors—Arthur C. Clarke, J. R. R. Tolkien, Stephen King—revised novels after their initial publication. Among smaller earners, John Barth restored the original ending of his first novel, The Floating Opera, after he had published three more novels. I expect the highly original Barth was afflicted with considerable zombie-inflicted guilt because he accepted his editor’s tacking a happy ending onto an essentially nihilistic story. Keever—I’ll blame this on him—sometimes fabricates happy endings for his “memoirs” in order to make the money he always seems lacking. I never expected to profit from those Keever books, so at least I don’t have that zombie guilt. (It may well be true, though, that I chose to work with an unliterary narrator so I could blame any of my stylistic infelicities on him. In Passing Again, Keever makes just this argument against the author.)

It’s too late for me to change those four novels. I’m hoping that publishing this essay admitting my zombies will somehow diminish their presence in my brain. But I write not only for myself. I’m also writing for other novelists and for readers who may think of novelists as arrogant big-brained creators whose long-considered and refined works make readers feel inferior about their own discourse. I think I can assure you readers that—since Nabokov is dead—every writer knows a zombie or two. The next time you read an interview with some supercilious, egocentric author, try to have some empathy for them, because you know the author’s secret: the curse of the zombie book.

* * * * *

Second Acts

by Tom LeClair

Fitzgerald’s famous line—“There were no second acts in American lives”—may have been misunderstood for decades. Instead of asserting there were “no second chances,” Fitzgerald could have been referring more literally to the theater. Instead of following the traditional three-act play, in which the second act furnishes complications and conflicts, American lives may quickly move from exposition to climactic defining actions—as Fitzgerald’s did with his early (and damaging) success. My title refers to both acts and actions.

Fitzgerald used the phrase “no second acts” in an essay about New York entitled “My Lost City.” In 2008, when I was 64 and retiring after 38 years as a professor of English at the University of Cincinnati, my partner and I sold our three-storey house in Cincinnati and bought a two-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn. “People don’t retire to New York City,” I was told by friends in Ohio. Even acquaintances in New York were skeptical, but my partner and I wanted action. Not “The-City-That-Never-Sleeps” action but something more literal, physical, specific. At 47, she was just getting started with the martial art capoeira when her mestre, the only one in Cincinnati, left the city. I was just beginning to play table tennis, after decades playing basketball, and I had seen the intense competition in Chinatown on a couple of visits.

We told friends that we were moving for “athletic opportunities.” They misheard “aesthetic opportunities” for me. They assumed I wanted to be near the venues for which I reviewed new books, close to agents and publishers who might be interested in my novels. Although I knew a couple of novelists in the city—Don DeLillo and Joseph McElroy—and met Jerome Charyn at a ping pong club not long after arriving, none of them introduced me to their agents. I gave a pong lesson to my long-time editor at the New York Times Book Review, but that didn’t stop him from cutting me loose when I turned in a negative review of a writer the Book Review thought important. I bought lunch for an editor who paid me well for online fiction reviews, but he ultimately decided I was too “exacting.” Living in Brooklyn with other scribblers offered occasional literary pleasures, but I didn’t move there for career opportunities.

If New York was lost to Fitzgerald, it was my found city, my fond home for twelve years. My partner, soon to be my third wife, my third chance at matrimony, had lived in New York for a few years a decade before. For her, a disgruntled native of Athens, a disaffiliated resident of Cincinnati, returning to New York was a second chance to live in what she felt was her true home—near relatives and plenty of capoeira schools to choose from. I used to kid her that capoeira was a cult when in fact it was merely—compared to my obsession with action—a passionate hobby both physical and mental, one that took us one year to Bahia in Brazil to visit the near sacred source of this most graceful martial art. Unlike my partner, before moving to Brooklyn I had never spent more than a few days at a time in the City and only a few hours in a basement ping pong club near the corner of Canal Street and Broadway, but Robert Chen’s New York Table Tennis Foundation soon became my home away from home, an energizing source like Bahia. Though far from sacred, the club did rent out space on Friday mornings to Muslims who needed a place to pray.

Maybe my word “obsession” is not strong enough. The older I got the more I subscribed to an archaic distinction between those living and those not: the quick and the dead. To reword Hamlet, quickness, not readiness, is all. I don’t know how I came to think of my life in those terms. Yes, I played basketball from the age of eight to 50, and as an adult I was almost always the smallest and weakest person on the floor. I needed to be quick and, against conventional opinion, taught myself to have quick feet and hands, and even quick eyes, peripheral vision to find the open man. When I had a second professional act in Ohio—switching from writing criticism to fiction—I gave my quickness to my pro hoopster Michael Keever and eventually wrote four more novels about him and his obsession with the quick and the dead.

Some people from the provinces come to New York for the speed of life, the action in the parks and clubs, in the trains and streets. Of course, I enjoyed all of it, a near constant environment of quickness, the famed “New York minute,” but no matter how fast the streets were nothing was like the demand exerted by that little cellulose ball traveling 60 miles an hour across a 9-foot table. For quickness, competition was necessary, and there was plenty in Chinatown. The best I can do in analyzing my desire for quickness is to say I wanted to surprise myself, as I did once in a while when playing basketball. I wanted to feel that my brain and reflexes were faster than my thinking, possibly faster than the actions of the 20-year-old across the table from me. In my worst moments, I see myself at the table as a senior vampire, sucking the life out of the much younger and quicker people I most enjoyed beating. Surprise myself, surprise others, prove to myself I remained among the quick.

Make that a “white senior vampire.” I was often the only white guy in pick-up basketball games. The same was true in Chinatown. I always dressed the part of the flyover country rube, what club players call a “garage player.” I wore my basketball Nikes instead of Mizunos, gray tees rather than garish pong shirts with exotic paddle-maker logos. I used the term “ping pong” instead of “table tennis.” “Bring ’em to you, fuck ’em up,” my hoopster is told by one of his coaches: create and then use your opponent’s false assumptions, his or her overconfidence. Atanda Musa, the legendary Nigerian player and coach in Chinatown, wanted to improve my strokes, but I stuck with my unorthodox swings that didn’t impart the spin that trained players expected. I surprised some people and myself, but there’s an iron law in table tennis: the player with the earliest coaching and best mechanics almost always wins. I knew that before I moved to New York, and in Chinatown I accepted it for the sake of many years of almost daily quickness.

Second home, second sport. I know that my need for quickness is anomalous, that my late-life ping pong probably won’t bring you to the table, but I like to think my years of New York pleasure might encourage others—young or old—to imagine seeking other homes and new actions. What I did not anticipate was that ping pong in New York would lead to my second act in which—contra Fitzgerald on drama—Professor Emeritus LeClair became the character Professor Ping Pong in a long-running show a block from Broadway.

While playing in Chinatown, I met the three young filmmakers who, with Susan Sarandon’s and others’ money, opened the SPiN ping pong and social club, which has now been franchised to several American cities. They needed a scorekeeper/referee for their Friday night professional tournament that attracted with good prize money some of the best players in the country and from abroad. When the owners found out I had been a professor, they figured I could provide some senior-citizen authority and, perhaps, comedy. The filmmakers wanted me in costume, wearing a bow tie (I had to buy some), suspenders (also needed), button-down Oxford shirts, and baggy pants. I sat next to the tournament table and kept score on a laptop that showed the matches’ progress on monitors throughout the club. Only Ms. Sarandon, who sometimes sat next to me, was anywhere near my age in SPiN, so I added gravitas to the youthful proceedings—the quick-hitting action at center court, the date-night interactions on the other tables, where I used to mingle and greet and sometimes hit a few balls with customers between tournament matches.

Gradually my seated role became a standing act. To break up the tournament, SPiN created audience-participation activities. For the “runaround,” old PPP would pretend to limp out to the table and would stand at one end. People would line up at the other end. I would hit an easy ball, the first in line would return it (or not), and run around to the end of the line (or not). The participants had few skills so many dropped out early, but at the end maybe three players remained to quickly run around and around in order to return the ball to me. To entertain the mostly male audience, I was encouraged to keep the best-looking young women in high heels scrambling around the table after I bounced out their brofriends.

Anyone with intermediate skills could manage the runaround. Professor Ping Pong became known for the “serve return.” Again the audience participants—maybe 30 of them—lined up across the table from me. They had one chance to return my serve back on the table—not win a point, just get the return on my side of the table. In Cincinnati, I had a table in my attic and practiced serves for hours. Even intermediate players in Chinatown had problems with my vicious side spins at first. The alcohol-addled customers at SPiN had almost no chance. It would be weeks before someone—usually a ringer who had taken some lessons—got my serve back. A few customers would return Friday after Friday for another chance. Again the models and would-be models that came to SPiN had the best chance of getting an easy serve and winning the prize of a free drink. If I had been a hapless-appearing old man when playing in Chinatown, at SPiN I was a lecherous-appearing old man who favored the “girls” like these visiting Romanians, one of whom “won” a drink.

After some years, I wanted to top myself so the serve action became a different kind of act, a pretense with a prop. I had a black loosely knit wool scarf that I could see through. I tied it around my head and pretended to hit serves blindfolded. Surprising, even amazing, and still unreturnable. SPiN was run by and for people in the performance business. Ms. Sarandon was usually there on Friday nights. Judah Friedlander with his “World Champion” cap was a frequent and welcomed attendee. One afternoon at SPiN I killed Woody Harrelson. I played with Ethan Hawke’s young son and Danilo Gallinari of the NBA. I kept score for a Justin Bieber match. Terrell Owens of the NFL refused to play me. I gave a lesson to the writer Geoff Dyer. My black-scarf magic act was just part of SPiN entertainment, the comedy of a “blind” old man dominating the young, reversing the action of traditional drama. What did bother me a little about my second act was that after my five years of Friday nights at SPiN probably more people knew me as Professor Ping Pong than as the professorial author of hundreds of reviews and a dozen books.

If you put yourself in motion and have a little luck, you may find yourself in the right place at the right time for a second act. Not necessarily in New York City, though my third act could have happened only there. In 2016, I was in the right place in a wrong time. The day after Trump’s election, I went to Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue with a cardboard sign that read RAGE TRUMPS HATE. Every day—including Christmas and New Year’s and Inauguration Day—I stood for six hours with different signs in front of the Tower. At first, I was a solitary protester. Then two middle-aged guys selling anti-Trump pins joined me, and after a few weeks another sign holder came, a retiree like me enraged by Trump’s election. All semioticians, we named ourselves “The Four Horseshitters of the Apocalypse.” The other three called me “Professor Protester” because I dressed formally against the cold and my signs were often literary, allusive, and too subtle—the others said—for the passersby. I wanted more than a quick glance and thumbs up or thumbs down from the thousands who walked past on Fifth Avenue. I wanted to bring the natives and tourists to me for a conversation and photo of my sign that they would circulate on social media, thus extending my reach and even recognition. The next summer a woman from Florida walked up to me and said, “I saw you on Facebook. I came by to see if you were still here.” I don’t remember seeing any celebrities except for a couple of former NBA players: I got a wave from Vlade Divac and talked briefly with Antonio Davis whom I’d seen playing in Greece and who was the model for a major character in Passing Off.

My signs also attracted the attention of the media that swarmed the area those first months. I was interviewed by Japanese TV (twice), Swedish TV, radio stations from the U.S. and abroad, and various print media. Again, I was probably more widely known for what I said than for what I had written. This bothered me not a little because I hated—no act, no pretense—what Trump and his minions were doing to American democracy. One of my signs, targeted primarily to tourists, sums up my message: TRUMP TOWER IS NOT AMERICA. IT IS BABEL, COMING DOWN SOON.

Stamping my feet in the cold, shuffling up and down the sidewalk when harassed by the police, I abandoned ping pong quickness, and yet I felt quickened emotionally and intellectually, particularly when arguing with—competing against—the occasional Trump loyalist. I never came close to getting in a fight over ping pong. Protesting took me back to my basketball days—physical competition, pushing and shoving, screaming and cursing. As interest in protest waned, my signs became more aggressive and I became more active. I encouraged, as at SPiN, audience participation. I invited passersby to join me in a photo op: stick their hand through a hole in my sign and have a friend snap us giving Trump the finger at what I identified as the “official site” for doing so. For more action, I asked pedestrians to join me in stomping up and down on a Trump banner I bought. When the “Naked Cowboy” came from Times Square with his anti-Semitic rhymes, I got in his face and interrupted his Trump-friendly act.

Looking back now, I see those first months at Trump Tower as the most consistently intense period of my life. I was even more obsessed with my protest act than I had been with ping pong. Whatever the weather, I felt compelled to be in front of Trump Tower. For playing Professor Ping Pong, I was paid. Professor Protester refused cash offerings of support. After the pretense at SPiN, I wanted my act at Trump Tower to be pure. As Eliot puts it in his poem about an old man, “Gerontion”: “I would meet you upon this honestly.”

In the months after the inauguration, I came more sporadically to Trump Tower. Many days I stayed in Brooklyn and wrote the essays in Harpooning Donald Trump, a book that was published in 2017 by a man I met, somehow fittingly, playing ping pong. The book would never have been written had I not put myself in motion, left my warm study and did yet another stand-up routine for the crowd. The essays related my experiences at the Tower and said what Professor Protester could not fit on his cardboard signs: historical, psychological, and literary analyses—and condemnations—of the Trump phenomenon. With my third act, a circle closed—from a writer of literary criticism in Cincinnati to a writer of cultural criticism in New York City.

My move to New York may have been something of a whim. My second act as Professor Ping Pong was a lucky break. My third act as Professor Protester was more consciously willed, and yet all had their source in action, in motion, doing something without knowing what the consequences would be. Ping pong required quick hands. Sign-bearing required quick wits. You need not be quick or become a public performer to prove Fitzgerald wrong. Perhaps your second act will be slow cooking or Zen gardening. Years before I went to New York I had published a novel, The Liquidators, in which the narrator/protagonist comes to believe at the end of his faulty life that “surprise is sure.” Even now I wouldn’t say “sure,” but after I wrote that line I found surprise was possible. If for an old man like me, perhaps for you.

In the spring of 2020, I made a quick decision to put myself in motion again, to leave my wife and New York to live for a year in Warsaw with a Polish photographer half my age. Now we are living in London. I haven’t played ping pong in months, and I no longer write about Trump. I thought that when I abandoned New York I was done with writing, but in pandemic-locked Warsaw I surprised myself yet again and wrote Passing Again, part novel, part memoir, a “record” of what may be, at age 77, my fourth act—leaving the found city I loved, finding a new life as Professor Peripatetic, a two-suitcase nomad with no home and with no public performance. Except, perhaps, this mini-memoir. My body is no longer quick, but that’s not as important to me as it used to be. I do still occasionally wear my “SPiN New York” tee shirt.

Pynchon, the Pandemic, and Me

by Tom LeClair from The Daily Beast (2020-21)

Not long after the pandemic began, an editor at the website Jezebel titled her essay on quarantine reading “You Don’t Have to Read Gravity’s Rainbow During Self-Isolation.” She instead recommended “trash” or books one had read as a child. Others in lit biz were quick to recommend Camus’s The Plague, and a piece in the New York Times suggested Moby-Dick, mostly for its finale of nature —the White Whale—exacting revenge on Ahab and the rest of the humans (except for Ishmael) on the Pequod. Depending on how long the pandemic lasts, I, too, would recommend Moby-Dick—as a precursor of and as a warm-up for Gravity’s Rainbow where the killer whale becomes the killer rocket.

If it’s fiction you want during shut-in days, Pynchon’s is the American novel that offers the most profound understanding of how the pandemic is killing hundreds of thousands across the globe. Granted, each of us is most concerned that the virus doesn’t kill us, but you still might like to know Pynchon’s analysis—in 1973—of why you might die. And although Gravity’s Rainbow has a very pessimistic diagnosis of human history, that diagnosis might inspire the cognitive shift necessary for regeneration after the pandemic eases, if it does. Plenty of op-ed writers have offered cultural analyses and future prescriptions, but Pynchon’s fiction is further reaching, more imaginative, and more affecting.

Gravity’s Rainbow is also notoriously long and recalcitrant. But if you recognize its Brechtian “epic theater” as decidedly relevant to our current situation, reading it could be a good investment of your entertainment hours because the novel is an encyclopedia of humor, what scholars call “the carnivalesque.” Pynchon includes a Huck Finn-like Innocent Abroad as protagonist, a large gallery of fools and frauds, slapstick chase scenes, movie parodies, Catch-22 absurdities and Monty Python stupidities, as well as bawdy songs, Proverbs for Paranoids, and word play worthy of Nabokov, with whom Pynchon studied. I should also mention plenty of sex scenes to please just about every taste (and tastelessness). But be not fooled: the hurdy-gurdy carnival is present to conduct you into the big tent, where gravity-defying high-wire acts of human rocketry occur.

Also, be not afraid. You can finish Gravity’s Rainbow, as I told university students to whom I assigned it, if you just keep going forward. Don’t loop back to get every joke and resolve every ambiguity. The multiple story lines will cohere—and diffuse again at the end. By then you should be moved by the novel’s emotional heart, presented in scores of variations: children away from home and threatened in the night, Hansels and Gretels without, unfortunately, their happy ending. For decades, Pynchon the prodigal prodigy has been criticized for his lack of affect, but readers who aren’t exhausted by the book’s generous excesses should ultimately feel Pynchon’s disgust with and pity for the human virus: “‘Fathers are carriers of the virus of Death, and sons are the infected.’”

“Humans are the virus” is apparently a slogan Reddit Eco-Fascists use to rail against immigration and overpopulation. Pynchon’s viral tail and tale are much longer, summarized near the end of the novel: The “World just before men,” Pynchon writes, was “too violently pitched alive in constant flow ever to be seen by men directly. They are meant only to look at it dead, in still strata, transputrefied to oil or coal. Alive, it was such a threat: it was Titans, was an overpeaking of life so clangorous and mad, such a green corona about Earth’s body that some spoiler had to be brought in before it blew the Creation apart. So we, the crippled keepers, were sent out to multiply, to have dominion. God’s spoilers. Us. Counter-revolutionaries. It is our mission to promote death. The way we kill, the way we die, being unique among the Creatures.”

For Pynchon, humans are the “carriers of the virus of Death” because of two unique features: first is our foreknowledge that we will die. Because of this, and here Pynchon seems to be following Norman O. Brown’s Life Against Death, we desperate humans used our intelligence (that gave us foreknowledge) to invent ways of protecting ourselves and killing others, both human others and the threatening “green corona” of nature, the planet-wide other.

To dramatize the consequences of this anthropological and ecological vision, Pynchon sets Gravity’s Rainbow at the end of World War II in the killing “Zone” of border-broken Europe. Characters from all inhabited continents gather in this Zone to hunt the special rocket 00000 created by Nazi scientists, some of whom would soon move to the U.S. There are also glimpses of concentration camps and a reference to the atomic devastation of Hiroshima. Although about the twentieth-century murderous past, as well as human prehistory, the novel and its rocketry really predict the future, our present in which death can surprise us from the sky, flying in from very far away—from nuclear weapons launched by North Korea or from a virus launched by a diseased bat in China. Gravity’s Rainbow may be the first globalized novel, one that understands that the technologies that we humans devised to keep ourselves alive and distant from others can be superspreaders of mass death.

For Pynchon, rockets are not just weapons or carriers but symbols of all industrialism that mines the coal and pumps the oil (mentioned in the earlier quote) to build towers and fuel machines that seem to promise rising above the “living critter” planet Earth. When 00000 is fired in the novel, the rocket is both an act of murder and an act of suicide, for a youth rides within it to “no return.” Humans have been committing murder for millennia. It’s the suicide that our industries have now enabled on a planetary scale that is new. For Pynchon, World War II was just an accelerated incident in humans’ long-running global war on nature. If this seems a truism to all but Republican lawmakers in 2020, remember please that Pynchon was writing his environmental novel 50 years ago.

At the beginning of Gravity’s Rainbow, German rockets are raining down on London. At the end of the novel, rocket 00000 seems to be coming down in Los Angeles. On a globalized Earth, no populated place is safe. A character in The Matrix makes explicit, some 26 years after Gravity’s Rainbow, the effect of superspreading humans:

You move to an area and you multiply and multiply until every natural resource is consumed and the only way you can survive is to spread to another area. There is another organism on this planet that follows the same pattern. Do you know what it is? A virus. Human beings are a disease, a cancer of this planet.

Perhaps cancer is a more precise analog for humans’ relation to nature, since viruses are not really alive. In any event, both can destroy their host, bringing about the very death humans wanted to avoid as they depleted much of the natural world and then abandoned it to live in a megalopolis that Pynchon calls the “Raketen-Stadt,” the Rocket City. The coronavirus rocket came down in New York City and other densely populated centers. In the novel, children are moved out of London to protect them from the V-2 rockets. In New York City, the rich fled to their country homes. The rest of us were left behind and to our own devices like the abused and murdered children in Pynchon’s Zone.

Pynchon knew about the rich, the elite, the “They” who control technology, economics, and politics, who promise security to us, whom he calls the “preterite,” the unchosen: “‘Can They keep us from even catching cold? From lice, from being alone? from anything? Before the Rocket we went on believing, because we wanted to. But the Rocket can penetrate, from the sky, at any given point. Nowhere is safe.’” Pynchon even knew somehow about Trump and his administration, this pandemic’s “They”: “‘They have lied to us. They can’t keep us from dying, so They lie to us about death.’”

Symbols of globalism, industrialism, and monopolism, rockets also represent the human desire for transcendence, for death-denying immortality in the heavens that rockets pierce. Pynchon sees the rocket prefigured in the pointed steeples of American Christian churches that promise souls’ return “home” to God. But “no return” is the constant refrain in Gravity’s Rainbow. Like the ancient organisms that gave us petroleum, we die here and return only to the earth.

One of the novel’s last lines is a call to bring “the Towers low”—the rocket towers, the megalopolis towers, the sacred towers. After the bubonic plague in Europe, some cities built “plague towers” to memorialize the dead and thank God for “saving” the cities. The tallest is in the Czech Republic, the most famous in Vienna. Will towers of fealty and thanks be erected after the current pandemic? Or will humans come around to Pynchon’s position that no salvation exists in the heavens, that no He—or They—exists to deliver humans from a pandemic or from our suicidal destruction of our only home?

Student of cybernetics, artist of control and chaos, user of inherited words going back to the Puritans, Pynchon implicates himself as semiotician with a late reference to William Burroughs. He thought language, enabler of restrictive codes and official lies, was the destructive human virus, so he cut up sentences and fragmented texts. Before quoting from Naked Lunch, Pynchon says, “I know what your editors want, exactly what they want. I am a traitor. I carry it with me. Your virus. Spread by your tireless Typhoid Marys.” Though diffuse, sometimes obscene, and obsessed with addiction like Naked Lunch, Gravity’s Rainbow does not as radically attack as Burroughs did the death-dealing language virus, the carrier of cultural repetition and repression. Pynchon gives editors and readers more of what he believes they want—more amusement and a more consistent argument about planetary life and death. Those features are why he speaks to us still. The last words of Gravity’s Rainbow are a hopeful song, followed by the singalong request: “Now everybody—”.

Our children need not be told—now—Pynchon’s version of human history, but if there is to be a cognitive supershift—to prevent future superspreading— perhaps we should tell them the outlines of Pynchonian history and, when they are old enough, put Gravity’s Rainbow in their hands. I was persuaded by Pynchon’s alarm in 1973 and have lived with the possibility of apocalypse since then. I had not stocked facemasks and toilet paper, but I was also not surprised by the virus rushing across global skies much faster than Melville’s nature-avenging mutant whale could move through water. It is only now, when deaths have abated in my home country, that I feel I can write this “Pynchon told us so”—just as Melville did in more ambiguous terms in Moby-Dick.

The tragedy of Ahab is classical personal hubris. The tragedy in Gravity’s Rainbow is species hubris. That hubris is with us still, with us in our political leaders who refuse to accept that America is not exceptional, with anyone who refuses to accept that humankind is not transcendent but contingent and fragile, subject to agents that can be seen only through a microscope. There is no pot of gold at the end of Pynchon’s Rainbow. But there is possibly enriching human humility. We will need it in our Pynchonian future.

*****

Although I congratulated Pynchon for his humility, the essay you just read was not humble, a view of earth from on high, up where Pynchon’s rockets cross the sky. They crash and burn. Not long after the essay was published in the summer of 2020 by The Daily Beast, I contracted the virus. I survived and have come back down here to apologize, to tell a tale of nothing less than dumb fucking luck, and to caution those who may believe some place is secure. About safety, Pynchon was right: nowhere is safe from the rockets . . . or the virus.

In the late spring of 2020 I was a septuagenarian who shouldn’t go out to a grocery more than twice a week during senior hours. But I had none of the serious health conditions—the co-morbidities that killed so many of my neighbors in Brooklyn in the spring—so I decided to fly to Greece in June to beat the European Union ban on Americans. You can think of this flight as both guilty escape and romantic quest. I had been separated from my Polish inamorata for six months. She would meet me again in Greece, which had one of the lowest rates of COVID infections in Europe, much lower than in the U.S.

I tested negative at the Athens airport and marveled at how many Greeks were walking the streets without masks, were still kissing each other on the cheeks, still shouting into companions’ faces in outdoor cafes. I kept my distance, didn’t see friends, waited for my inamorata to show up. She had tested negative a week before, so we didn’t worry that we would infect each other. We wore masks when in sight of others (there were not many others at the sites and in the museums). We carried and used hand sanitizer. We took no mass transport, no boats, not even taxis. We walked everywhere, never ate inside, never sat in one of those overcrowded, shouting bars on Tsakalof Street in Kolonaki. We walked through the unmasked gauntlet there and congratulated ourselves on holding our breath.

“Hubris,” you probably know, is a Greek word. I’ve thought about it often in the forty years I’ve been visiting and living in Greece. I used to be amused at how proud contemporary Greeks were of their ancient heritage and presumed “racial purity.” I was entertained by other American visitors’ pride in being able to flush paper down the toilet in the U.S. Now I was proud of myself for rocketing out of America and sneaking at the last minute into a safe place. Then in mid-July, I started to have a low-grade fever. It went on for three days. “Yeah, okay,” I told myself—for the last few months since a Whipple surgery I’d been having intermittent fevers my surgeon couldn’t explain. But a Greek doctor friend insisted that I go to a government medical center and be tested for COVID.

And that is where I understood very quickly the U.S. State Department’s advisory against foreign travel in these times. “Anecdote” is also an ancient Greek word, one literally meaning “things unpublished.” What follows is anecdotal but may be worth reading, not because of what I have to report about Greek medicine but because being ill in a foreign land may usefully represent in heightened form the uncertainty and fear of being an infected person in America. As I said—this is a caution from afar for those at home. I don’t want to be hyperbolic, another Greek word, but in Athens I did come to understand the Greek roots of “pandemic”—“all people.” Any person, any place, any time.

The middle-aged Greek doctor who examined me at the center began by shouting at me: “You should never have come to Greece. You bring the virus from New York. What are you thinking?” I told him I tested negative at the airport more than two weeks before, but he insisted on my guilt even before he swabbed me. I told him about my history of intermittent fevers, explained I had no symptoms except the fever, said I felt I had a sinus infection. “No, no,” he said, “you have COVID and you brought it here. So now I send you to the hospital.”

“Before the test results?” I asked.

“Yes, I am calling an ambulance.”

I was aware that those suspected of being infected when they arrived at the airport were put in quarantine for a night or two until their test results came back, but the doctor insisted I be admitted to a hospital. I know Greeks who work in hospitals, I knew about the lack of basic supplies when COVID hit, and the general improvisatory nature of Greek doctoring, improved by a “phakelaki,” an envelope with some cash. I resisted going to the hospital, but the doctor said he would call the police if I didn’t agree. So my inamorata and I rode to the hospital in an ambulance, thinking, “Well, an abundance of caution.”

The hospital didn’t seem busy. I was taken right in and asked to lie on an examining table covered with the usual paper. It was wet from the previous patient. I refused. I was taken to another small room and lay on a table. About two minutes later, EMTs brought in a 50-ish man in serious distress, sweating profusely, struggling to breathe, eyes rolling. This man’s gurney was placed parallel to my table, no more than two feet from me. No barrier of any kind between us. That’s when I got up, walked out of the room, walked out of the hospital, and found a taxi before any police could detain me. My companion told me the distressed man had been kept in her small waiting room—almost as close to her as he was to me—before he was taken to my room. The hospital seemed more dangerous than the streets, so we went back to our Airbnb to await my test result. The next day it came back positive.

Greeks are proud of another ancient word: “philoxenia,” “friend to a stranger” or hospitality. We messaged our host, told her I had tested positive, that the Ministry of Civil Protection told us not to leave her apartment. The host was even more xenophobic than the examining doctor. She threatened to bring some muscle who would remove us immediately from the apartment; she then said she was calling the police to evict us. She accused us of faking my result so we could stay in her apartment longer. Only the intervention of an officer at the American Embassy prevented conflict at the doorway the day I got my COVID result.

The next morning the Ministry transported us to a quarantine hotel in an ordinary van driven by a man with a paper mask. Ambulance to the hospital before test results; van ride after testing positive. Just one example of the inconsistencies in Greek protocols, if they existed at all. We spent two weeks in a small hotel room with a balcony that offered a view of the Aegean—if you could bear the traffic noise to stand out there. We were never to leave the room. Food was left outside the door three times a day. No medical personnel dropped by the hotel to check on our health or the health of other residents. A desk clerk did go to a pharmacy and bought me an oximeter. I was in e-mail contact with my doctor friend, but he was not allowed to come to the hotel and examine me. I never knew from hour to hour, day to day, when the fever might spike, when I might develop respiratory problems, when I might have to be hospitalized in the kind of place I’d bolted. Add an even worse fear: that my companion would be infected by me, have to go alone to a Greek hospital where I could not help her.

She did not get infected. I never had symptoms other than the constant fever and attendant brainlock. Like I said, dumb fucking luck. After our fourteen days, we walked out of the hotel without any further testing. That was the “protocol.” We flew to Poland and paid for tests the next day. Both were negative.

Here’s my caution, if you need encouragement to continue wearing a mask. Many Americans ride out a light case like mine at home. But if you are confident in your youth or proud of your good health or have faith in your luck, please imagine yourself COVID positive in a foreign country with a person you love. Imagine what the fear would be like in that hotel room for two weeks, try to imagine separation from your doctors, from your family, from what you ordinarily eat. I find it impossible to imagine being on a ventilator. Maybe you do, too, so put yourself in that hotel room, possibly alone. The traffic noise on Poseidonos Avenue near Glyfada was horrible, and yet in the wee hours I felt I could hear the wings of the Angel of Death fluttering out on the balcony. No matter where you are, you, too, may hear the Angel outside your room.

I’m not asking for your sympathy but hoping to elicit reasonable fear—not by placing you in that Greek hospital but by ramping up the fears you may experience even if you should have a light case of COVID. You may be at home, but you won’t feel it is safe. I still believe most of what I wrote in that essay on Gravity’s Rainbow. I don’t believe COVID came after me because of my lack of humility, my smart-ass “Pynchon [and I] told you so.” But I do regret my earth-from-above tone. So some very down-to-earth advice: If you want to test your luck as I did, buy lottery tickets. I tried to socially distance myself from a New York with bodies in refrigerator trucks. But one last time: no place is safe. Wash your hands, avoid all the things I love about Greeks—their sociability, their intense talk and passionate touch, yes even their in-your-face pride at being a special people. I never thought being in Greece would teach me humility. I should have remembered what happened to those with the virus of hubris in ancient tragedies. The tragic characters wore masks that did not protect them from their pride. Be humble, wear your mask, get vaccinated.

Pynchon has often been dismissed as a paranoid. I didn’t write this anecdotal apology to make you paranoid, only to elicit a certain experience of fear that could—I say maybe not very humbly—save your life if you’re not as lucky as I was. I did not beat COVID, as one athletic friend suggested. No, in the summer of 2020 my inamorata and I were passed over.

I am finishing this apology in London in the winter of 2022 while proofreading the “second” edition of Passing Again. Though it is set before the pandemic, I see now that the novel—written during the pandemic—was probably influenced by it and by Pynchon, his vision, in Michael Keever’s words, of the “long continuity with death,” with global death. And, more intimately, influenced by my luck surviving COVID and by my inamorata’s luck in not being infected. In the novel, the character named “Tom LeClair” is obsessed with taking one “last shot,” even if it’s a long shot, before the buzzer. Two feverish weeks in a quarantine hotel will do that to a septuagenarian, or maybe I should say “did that to this septuagenarian.” With some distance in time and space, I think that Passing Again is most fundamentally my personal “plague tower” expressing fealty to Fortuna. I have spoken about Passing Again as a game I wanted to play with and against the reader, but now I feel there was a deeper motivation for this last-shot “memoir/fiction”—and for this essay: to give thanks for all my late-life acts, my run of dumb fucking luck.